In the 1960s a new generation of Black abstract artists faced a double bind, caught between the commercial gallery system’s failure to acknowledge Black artists practicing abstract art, and established Black artists known for figurative work who shunned abstraction as a non-representational expression of the Black experience.

Despite these limitations of perception, a group of artists continued to push the boundaries of material and form and came to fruition during a time where acts of resistance were the norm. Ed Clark (1926-2019) was one of those artists, and in a show titled Expanding the Image at Hauser & Wirth in Los Angeles, we see the progression of Clark’s career as one shaped by and in response to the times. Born in New Orleans in 1926, Ed Clark was a product of both the Great Depression and the Great Migration, moving to Chicago where he continued to cultivate his childhood love for drawing. He would later study at the Art Institute of Chicago and in Paris after World War II under Roosevelt’s G.I. Bill.

When he first arrived in Paris in 1952 Clark was still painting figurative work, however that process left the artist somewhat unfulfilled. As he began to closely examine the properties of paint, distilling the act of painting to the material itself led Clark to an important career-defining revelation. His experimentation took his work from the easel to the floor, painting on paper and canvas using unconventional tools, most notably a push broom in a legendary process Clark called “the big sweep.”

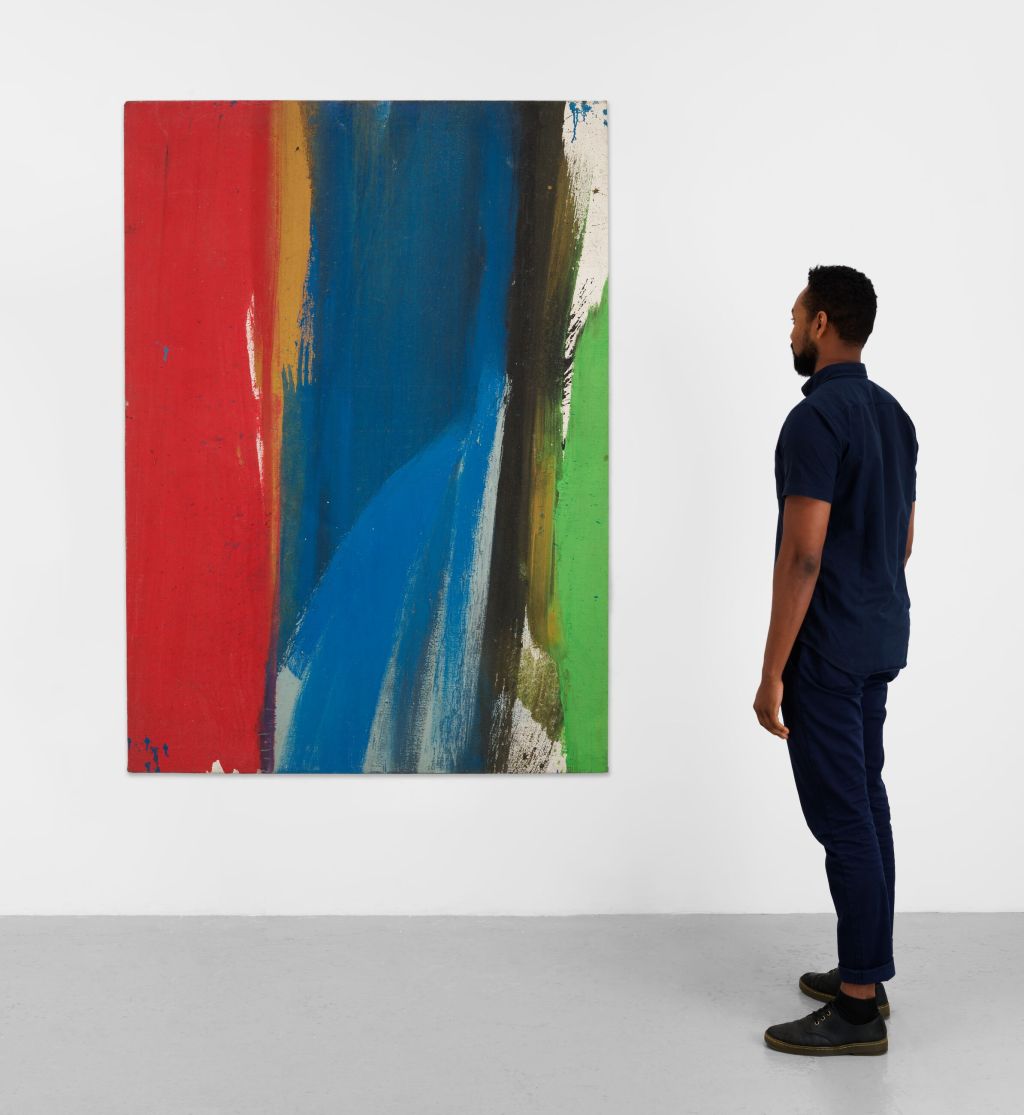

Using the push broom, the artist swiftly created broad, gestural strokes that significantly increased the scale of his canvases. Clark’s experimentation with paint and color became a rewarding process that gave him the freedom of expression that figurative works no longer offered. Among the paintings in Hauser & Wirth’s show Clark created between 1956-1969 we see large swaths of paint in bold, primary colors that span the horizontal and vertical planes. His 1963 work titled “Locomotion” experiments with these horizontal and vertical strokes as a study of movement across the canvas. The work is emblematic of the physicality embedded in Clark’s process that requires the engagement of the entire body movement to create big sweeps of color.

©The Estate of Ed Clark. Courtesy of the Estate of Ed Clark and Hauser & Wirth

Ed Clark’s daughter Melanca once remarked that the paint hues her father chose were oftentimes a byproduct of his access to material, however there were also indirect influences, like light for example, that were characteristic of the unique locales where he painted (France, Greece, Nigeria, the Southwest). When the artist visited his good friend Jack Whitten during the summer of 1971, Clark’s subsequent paintings were created in pastel shades, reflecting the soft, gradient lavender tones that yield to the dark orange streaks that radiate from a slow setting sun in a Mediterannean seascape. Studying these particular works in relation to the environments where they were created offers the viewer insights on the vast inspirations behind the artist’s work.

Courtesy of the Estate and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen

Some of his influences were subconscious, but Ed Clark’s career progression in light of them is an important lesson in abstraction representing a sum of an artist’s experiences over time. These insights enhance my appreciation for Black artists practicing abstraction. I have a deeper affinity for Alma Thomas’s works that reflect the light and the movement of leaves on the trees outside her studio window–I better understand Beauford Delaney’s love of the color yellow as an emotional salve–I see Melvin Edwards’ sculptural works as totemic symbols of resistance, and William T Williams’s connection to his family’s North Carolina roots in quilting are reflected in the geometry of his painting. While knowing this context adds to my appreciation for the work, they are far from being prerequisites for understanding it.

I think Ed Clark would have bristled at the idea that abstract art must have context or narrative explained for it to be understood. In the documentary, “A Brush with Success”, he once observed, “I’ve noticed when people sometime(s) ask, “what is it?”, and these are intelligent people (some of them), and I know what they are looking at–they are looking at something like a puzzle before it’s put together from their point of view. They think words can bring it into focus, but I usually say, “well, would you ask Miles Davis, what does that mean?” Much like jazz, the color, form, and movement embodied in abstraction evokes a feeling. While others may understand the intellectual complexity behind the work, others can appreciate it for purely instinctual reasons.

Abstraction is not accidental or haphazard. Curator Melissa Messina recently remarked that “abstraction is a language of reciprocity.” The artist and the viewer each bring their own unique experience to the work in visceral ways. The artist’s influences may not be readily accessible, but if you are lucky, just like jazz, the physical and emotional resonance that’s emitted from a painting will pull you deeper into the work.

Leave a comment